By Oritsemisan Okorite

For years, Nigeria’s economy staggered under the weight of distortions that rewarded insiders and punished the wider population. Billions of dollars were drained each year to sustain fuel subsidies—a scheme that, while politically popular, served more as a sluice gate for corruption than a safety net for the poor. It is estimated that over a quarter of subsidized petroleum products were siphoned off and resold across neighbouring countries, like Niger, Cameroun and Benin Republci. The system not only bled government coffers dry but also stifled private investment in refining, leaving Africa’s largest crude producer paradoxically dependent on imports for its domestic fuel needs.

The removal of fuel subsidies marked a seismic shift in Nigeria’s economic landscape, one that has begun to reshape the contours of the country’s long-fragile fiscal architecture. The long-delayed Dangote Refinery, a $19 billion private investment, finally gained commercial viability only after subsidies were dismantled, breaking the decades-old incentive structure that discouraged meaningful private capital from entering the sector. The refinery’s full operations, alongside others like BUA’s emerging facility, signal what could become a new era of self-sufficiency and value addition in Nigeria’s oil industry. The industry is one that is now attracting a growing queue of prospective investors.

But energy reform has been only one piece of a larger, and far more delicate, restructuring effort. Perhaps no reform has had more immediate impact on Nigeria’s macroeconomic stability than the unification of the country’s multiple foreign exchange windows. For years, Nigeria operated a convoluted FX regime where official rates differed sharply from parallel market rates, inviting arbitrage on a massive scale. The system bred opacity, discouraged foreign capital, and made genuine price discovery near impossible. In a country where businesses import a substantial share of their inputs, such volatility rendered long-term planning hazardous at best.

The harmonization of FX rates, though initially painful, has finally brought a measure of predictability to the marketplace. Businesses and investors can now enter contracts and structure financing with a greater degree of certainty that was previously unthinkable. The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and credit rating agencies such as Fitch and Moody’s have taken note, revising Nigeria’s outlooks upward in recent months. Moody’s, for instance, recently upgraded Nigeria’s outlook to positive, citing progress on fiscal and monetary reforms.

The newfound policy coherence has also emboldened portfolio and direct investors. After years of capital flight, Nigeria is once again seeing cautious inflows. International funds are re-engaging with Nigerian assets, while sectors ranging from infrastructure to technology have drawn fresh interest. Global oil majors, long hesitant to commit capital to Nigeria’s upstream sector, are now revisiting expansion plans under more transparent contractual terms. The ongoing overhaul of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC), now a commercially driven limited liability company, is improving governance in what was once one of the most opaque corners of the state.

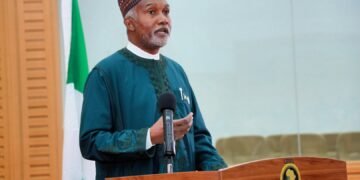

At the heart of this delicate rebalancing act is Nigeria’s Minister of Finance and Coordinating Minister of the Economy, Wale Edun, whose low-key but steady stewardship has helped hold together what could easily have unraveled under less deft hands. Operating mostly away from the limelight, Edun has worked to restore discipline to public finance, rebuild investor confidence, and coordinate often-competing interests within the government’s economic team. Under his watch, public spending is being re-prioritized, leakages plugged, and revenue collection strengthened. The government’s books, for once, are beginning to reflect both prudence and a seriousness of purpose.

Of course, the road ahead remains long and fraught. Inflation remains elevated, and living standards for many Nigerians are still under strain. The reforms have inflicted short-term pain—politically risky but perhaps necessary cost for long-term stability. Yet for the first time in many years, Nigeria’s economic trajectory appears to be moving not in reaction to crisis, but according to a deliberate, if difficult, plan.

Wale Edun, and his team must sustain both the political will and administrative capacity needed to consolidate these early gains Nigeria’s economy has made. For a country that has long been accustomed to financial instability, the emergence of a credible economic framework for growth as we are stilling under Mr. Edun is no small achievement.

Oritsemisan Okorite, a journalist writes from Lagos